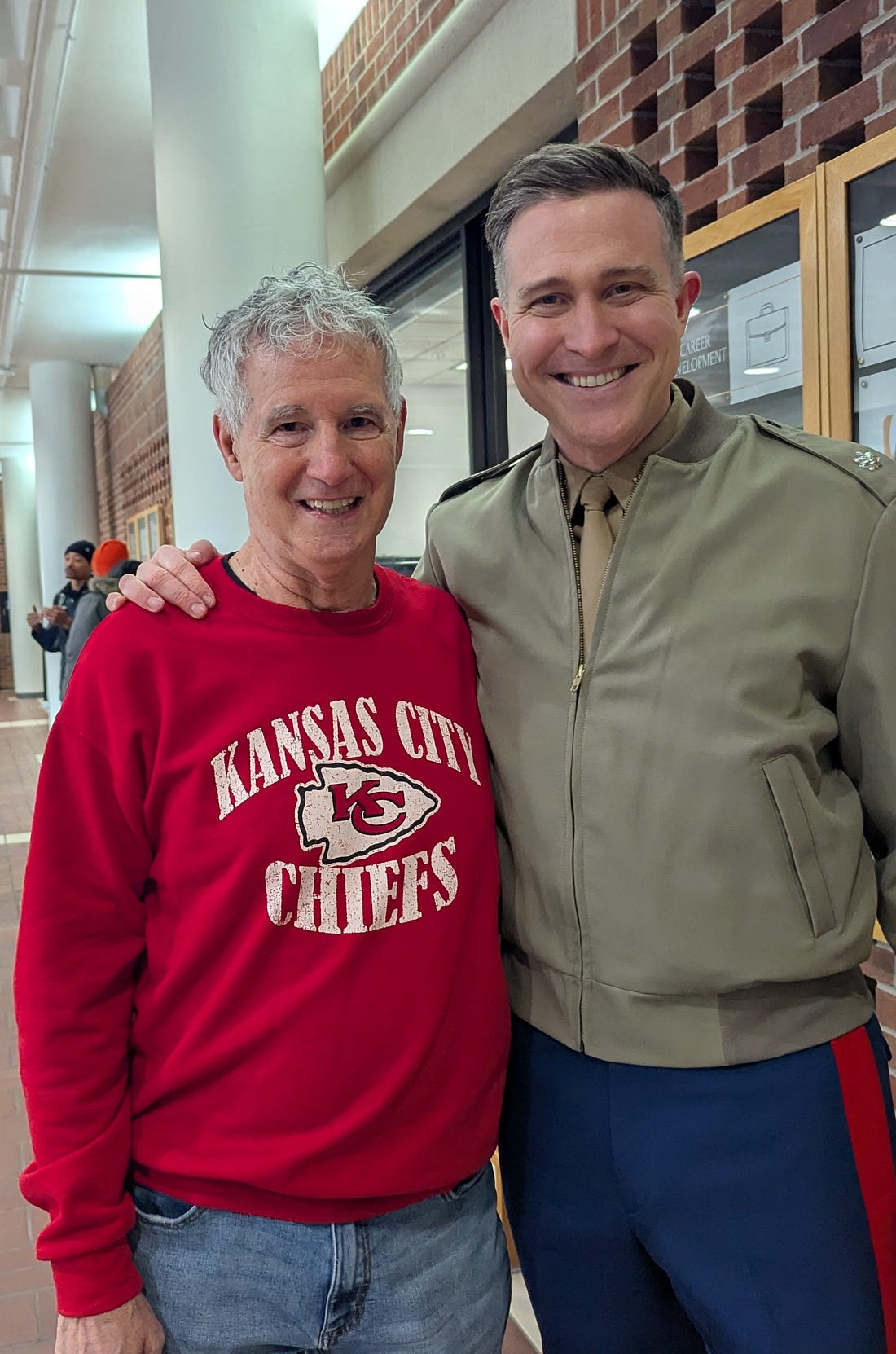

In my last post, I outlined some similarities between the present day and the McCarthyism crisis of the 1950’s, when President Kennedy published his famous book Profiles in Courage. In response to our current situation, and the obsession of some with America’s so-called “masculinity crisis,” I began a series of profiles amplifying just a few of the thousands of acts of common strength and resolve that play out across the fabric of Missouri and our country every day— quietly holding us together while our leaders seek to rip us apart. Examples that could dig us out of this crisis if only they got the attention or recognition that has instead been lavished on the dividers. I began with my best friend’s dad, a war refugee, and the strength he showed by moving forward rather than looking back. Today, the man who taught me what it means to belong to something, and how we could all use more of that in our lives. As many of you know, I was activated by the Marine Corps to serve at the Pentagon for the next few months. As part of those duties, I got to come home this week to Mizzou’s Law School to tell the students about life as a Marine Officer and attorney and see if any of them wanted to sign up.

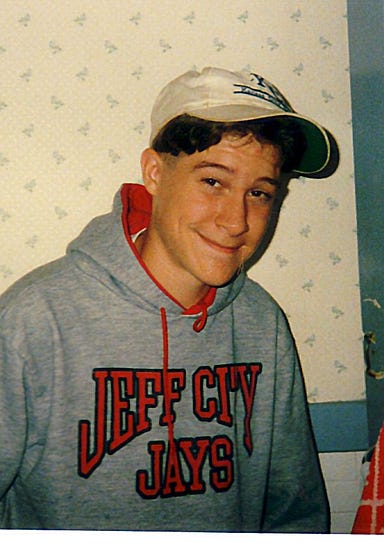

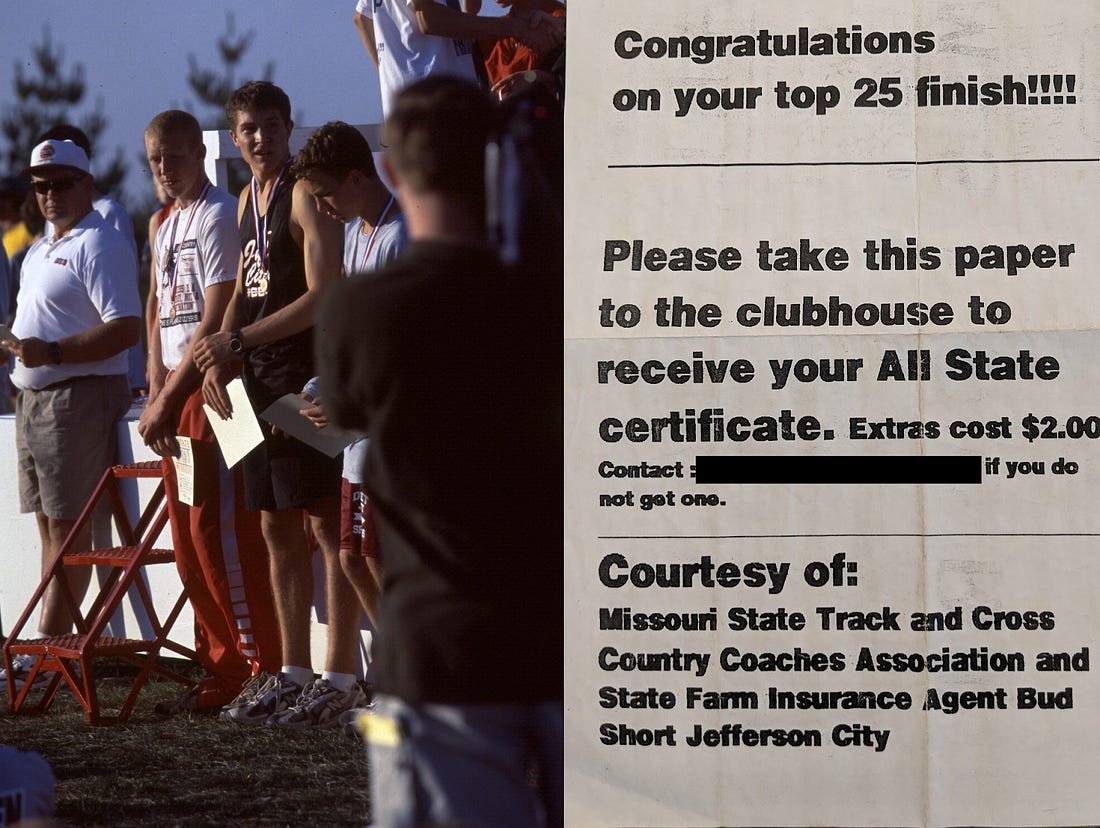

I was impressed at how much interest there was from the attendees and folks who just walked by. It was incredible to see how many from our younger generations want to serve or give back to the community. It was also disappointing to discover that almost none of them think public service is financially viable for them. Many felt forced to go in one direction when they would rather be doing something that they feel is more meaningful. Fortunately, I was able to let them in on what must be the world’s biggest secret: that being a Marine Judge Advocate actually pays well! The compensation package starts in the mid $100k’s, varying on when you sign up and where you are stationed, and it includes 30 days of paid vacation per year, all federal holidays, immediate courtroom action trying your own cases, VA home loans, the GI Bill, free healthcare for you and the family, etc. Plus money for law school, bar exam prep, bar dues, etc. Most importantly, it comes with a sense of service and belonging that is hard to come by these days. Interest went through the roof once people realized it was a viable choice. And it was obvious from the engagement that most of these kids wanted to get out and see the country and world, mix with others from all over, and do something meaningful. As much as I love the military and what it has made possible for me, which I wrote about in Running for Office as a Normal Person, I think me should have a multitude of options for public service with decent pay and benefits. I suspect one of the things causing our country so much pain right now is that it’s much harder to feel like you belong to something real anymore. Social media is so isolating, and pushes all the wrong things. Corporate America has sacrificed everything to maximizing shareholder profits. Small businesses have been gutted by consolidation. Communities are divided. I was lucky in my life to get that sense of belonging and purpose as a United States Marine, but even luckier to have discovered its importance in High School, so that I could look for it later in life. Here is the story of how that happened, and the man who made it so. “I’ll be alright,” I said, flinching as I put a bag of ice on my shin and leaned back against a Jeff City High School locker. Coach looked down at me and pursed his lips. “I’ll be right back,” he said Two minutes later he returned and held something down to me. I looked at his hand and back to his face, confused. He was handing me one of those paper concession stand coca cola cups. “Thanks, Coach…” I said, confused, “but I’m good.” I nodded toward my water bottle. He lifted the cup back up to himself, tilting it sideways as he did so. Sitting right below him, I jerked instinctively, expecting cold water to pour down on me. But nothing happened. Bemused, I watched as he ripped the paper rim right off the cup about three inches down. Then I laughed at myself. The water was frozen. With the rim torn off, it looked like a giant push pop sticking out of the tattered end of the cup. “This won’t fix things, but it’s better than the bag,” Coach said, “Do it like this.” And he rubbed the icy end up and down his arm then handed it back down to me. “We’ll figure this out,” he added, pointing at my shin, and walked away. It was the fall of 1998 and we were a third of the way through my junior season of high school cross country. For the first time in my running life, I was injured. But I knew that Coach, who had been there from my first high school run, really would do everything he could to figure it out. Just like my academic career, my athletic performance at Lewis and Clark Middle School had been entirely unremarkable. I’m pretty sure the middle school coaches only knew who I was because I had gotten my ear-pierced in seventh grade and my mom gave them hell when they made me take it out and it grew over. I had decided to run cross country freshman year of high school on a whim, basically because my super cool older cousin ran cross country and I didn’t really have anything else to do that fall. What a decision. On my first run, I paired up with a guy named Randy and we were given directions on where to run. It could not have been longer than three miles, but we stopped and walked every few of minutes, thinking we were dying. We would have walked a lot more except that the girls team started on the same route a few minutes after we did and, after their leaders tormented us as they flew by, we didn’t want to be caught walking by the rest of them as they all caught up and passed us. Miraculously, by the first meet Coach had us freshman to a point where we could at least run a full two mile freshman course without stopping. And midway through the season he had us on the occasional slow run with older guys, who we both worshiped and were terrified of. They were crazy fast — under Coach’s leadership we had become one of the top teams in the largest division in the state. But they were also just plain crazy. They used to pick up discarded beer cans on long country runs and drink whatever was left in them. They chewed dip when no one was looking and gave us nicknames like “Buddy,” “Daisy,” and “Ep.” They tried to name me “Dammit,” like, “dammit run faster” or “dammit get over here,” but Coach didn’t let that or several more offensive labels related to the pronunciation of my last name stick. By the end of freshman year Coach had me running 5k in under 18 minutes, which wasn’t half bad. I might have been a varsity runner if we hadn’t been state champions that year. I tore through sophomore season and aspired to be an all-state runner like so many of the older guys. Despite leading a team that was ranked as high as 13th in the nation that year, Coach took the time to make a plan for me so that I could make it happen the next year. The summer before junior year I crushed the miles like never before and just knew we were going to make it happen. The first couple of meets made me even more certain. But then, as the mileage piled up, my shins started to break down. I’d never experienced shin splints before, so I ignored it at first, as something I could just run through. This, of course, just made it worse. One day, Coach spotted me limping during a workout and immediately stopped me. I took the next day off, but it didn’t make a difference. Shortly after he gave me the ice cup, Coach came up with a new plan to at least keep me in the mix. He got me access to the YMCA across the street from the high school. Until things got better, I ran in the deep end of the pool with a floaty belt every morning before school and was either back in the pool or on a bike each afternoon. I spent the rest of the season in and out of the pool. A doctor told me that my feet were different sizes, so maybe I could try getting the right size for each rather than splitting the difference. This came across as pretty ridiculous given that my parents could only afford one pair of shoes for the entire summer and fall as it was and everything I earned went toward gas, lunch, and saving for a beat up old car so that I could get to work and school on my own. I told Coach about the situation and we tried some inserts instead. They didn’t do much. Coach’s pool regime worked fairly well. I ran the post-season that year and helped our team medal at the state meet. And although I didn’t make all-state, I had a good showing for a guy who hadn’t run in over a month, and scored in a year where we won a 4th place State trophy. As senior year came around and I amped up my mileage that summer, I freaked out at every twinge in my shin. I told Coach about it and he told me to ice early and often and not to worry about it. He said he would take care of things, and he gave me the occasional morning off so I wouldn’t get too worn down. I began the year even better than the year before, but the nagging thought that the mileage would catch up was always there. I brought it up again and Coach looked at me firmly and said, “Lucas, don’t worry about it. I’ve got it figured out.” A couple weeks later he asked me to stay after practice. So I did. He avoided eye contact with me as everyone else headed out. I started to develop that knot in my stomach that you get when you know you’re in trouble for something. I wondered what it could be. He waited until everyone was gone. Then he called me over to the storage closet in the hallway where he could talk without anyone overhearing us. My stomach churned. What had I done this time? Coach turned toward me as I walked through the door. I guess I was going to find out the hard way. I stood there awkwardly and waited for him to talk. I had learned that strategy the hard way when dealing with my mother. Always better for the adult to go first when you’re in trouble. “I want you to have these,” he said quietly, “but you can’t tell anyone. Do you understand?” “Huh?” “I’ve been tracking your miles. You need to change your old ones out. But I know… well… everyone’s situation is different. Just take these and don’t tell anyone.” He shoved a cardboard box into my hands and walked out, not waiting for me to say thank you or see what it was. As he walked away I looked down. It was a new pair of running shoes. I never would have achieved that without Coach. I may have never made it to Yale without the credentials he helped me earn. Or had the confidence that comes from knowing people have your back. That simple act, which I’m sure was against some rule somewhere that makes life harder for people without money, likely changed the course of my life. And it’s not like Coach did that for me from a place of comfort. He was a middle school teacher and high school coach in a state that pays its teachers poorly. And yet, he did big and little things like that for all of us. Most importantly, he gave us a sense of belonging and a place in the world. He taught us, from day one, to take care of ourselves and each other. That we always ran as a pack. Our Cross Country team from that era is being inducted into the Missouri sports hall of fame this month. And we couldn’t be prouder. We all still feel like we belong to it. And many of us, including me, have our place in this world because of Jim Marshall, one of the most selfless people I have ever known. Lucas Invite your friends and earn rewardsIf you enjoy Lucas’s Substack, share it with your friends and earn rewards when they subscribe. |

Saturday, February 8, 2025

America's Masculinity Crisis Ch. 2

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment