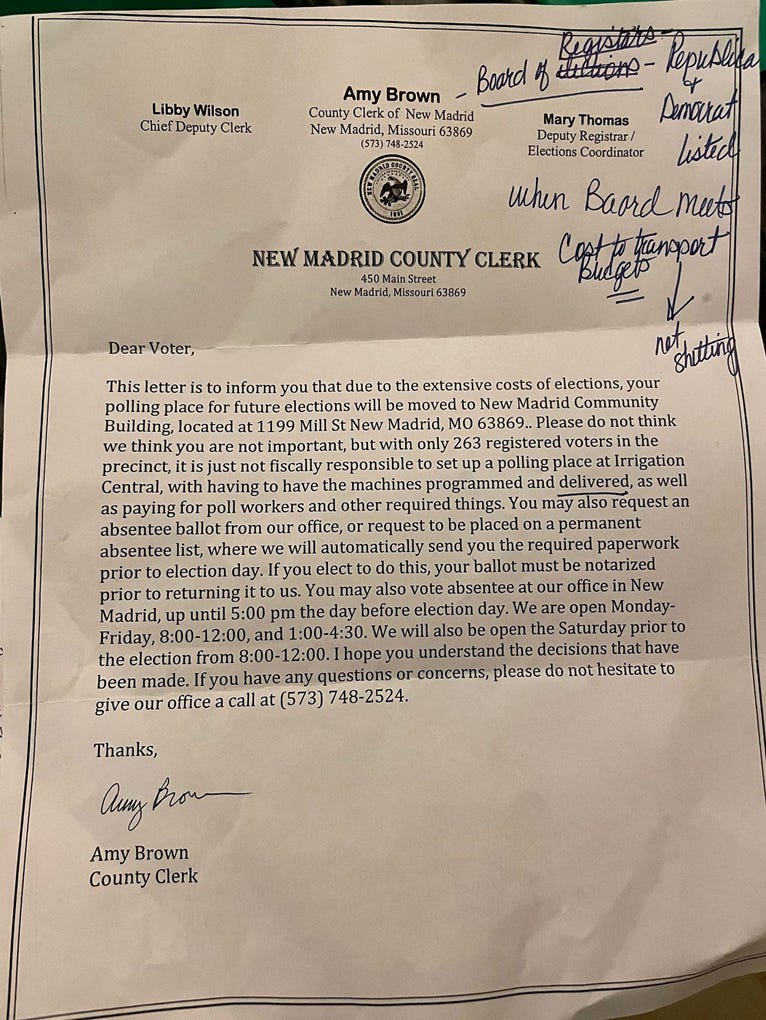

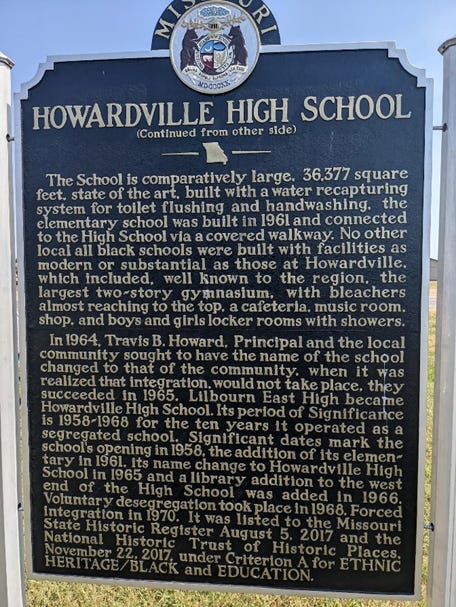

“Please do not think we think you are not important, but…...it is just not fiscally responsible to set up a polling place.”“Please do not think we think you are not important, but…” Two years ago, during my campaign for US Senate, I spent MLK Day in a mostly black town (92%) called Howardville. It’s in Missouri’s far southeast “Bootheel” region, the same area as Hayti Heights, another all black Missouri town whose struggles with clean water and sewage I wrote about a few weeks ago. In the spirit of Dr. King, my friend and Howardville resident, Vanessa Frazier, had gathered a group of other local residents together to figure out how they could protect their access to voting, which had recently taken a serious blow. You see, Vanessa, and everyone else who lived in Howardville, had received letters telling them that their polling places had been shut down. The letters read: “Please do not think we think you are not important, but with only 263 registered voters in the precinct, it is just not fiscally responsible to set up a polling place…” A third of polling places were closed in New Madrid County, a county that stretches across 700 square miles. It was another reminder that Dr. King’s fight for the democratic and economic empowerment of everyday people is far from over. With zero public input, Howardville residents were told they’d need to travel miles and miles just to vote — as would hundreds of their other friends in nearby towns. At the meeting, many residents said that they or their neighbors don’t drive and that the voting alternative for them was a joke: an option to vote by mail—with a notary—which most people there said they had no access to and which added another layer of burden to voting. People from all around the area showed up at Vanessa’s Howardville MLK Day event to talk about how they were blindsided by this. Republican and Democrat. Black and white. If you’ve ever seen the movie Braveheart, the leadership in Missouri followed the same strategy as the English king at the Battle of Falkirk, firing indiscriminately into an infantry melee to take out as many people as possible, regardless of their side: “Archers” The reasoning: the English king had more total troops than the Scots, so an equal depletion in numbers favored him because it increased the ratio in his favor. And besides, they were just poor commoners, so who cares? Welcome to the strategy behind modern voter suppression. A theme in Howardville that MLK day, a day we should have been celebrating equal rights and the legacy of Dr. King, was that the deck is still stacked against the Howardville community. Just like it’s always been. Here they were, in the 2020s, battling local leadership that thinks they are irrelevant, to try to retain access to voting. Howardville residents talked about growing up attending local segregated schools nearly fifteen years after the landmark 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education ruling, because the local leadership of that era felt the same way. One of those old school buildings, now falling apart, is actually on the national register of historic places for being such a late segregated school. The right is obsessed with DEI these days. Because it seems unfair. And it feels unfair. You know what else feels unfair? Being born black in America. Because Howardville and Hayti Heights aren’t exceptions or outliers. A lot of the time we think of racism as big acts or overt actions. And while these exist, perhaps the deepest impact of race in America is that it works a lot like a casino. The odds of you having a good outcome in any given situation are always worse if you are a minority, particularly if you are black. And these small disadvantages compound over time. Healthcare is a good example. Black infants are more than twice as likely to die as white infants. Black moms are more than twice as likely to die as a result of childbirth than anyone else. They’re also more than twice as likely to die from breast cancer. Your doctor is less likely to respond to you. Your provider is less likely to listen to you or prescribe needed medication. And even less likely to believe what you tell them. And forget about hiring. Just having a black name makes you significantly less likely to get a call on a job application. Even crazier, white men with criminal records are more likely to get a job application call-back than black men without criminal records. Does that sound fair? That doesn’t mean there aren’t financially well-off black people. A lot of black Americans have worked very hard and used a lot of talent to overcome the odds. Many of them supported me on the campaign trail. Developers, business leaders, engineers, doctors, you name it. Giants in their fields. And a common theme in all of our discussions was that they just wanted the next generation to have fair odds. When I was a young man I got pulled over quite a few times, for running stop signs, for speeding, and other things. Those tickets would have broken me if I had gotten them all, but despite being pulled over 10 times in a two year span, I only got one ticket. In a multiyear study of more than 60 million traffic stops across 20 states, Stanford University’s Open Policing Project found that black drivers are not only more likely to be stopped than white drivers, but that black and Hispanic motorists are also more likely to be ticketed and have their cars searched for less cause than whites. There have even been reports of local authorities freely discussing and making light of violence against black people, and actually advising recruits to shoot young marijuana users if they’re black. On April 4, 2015, an unarmed black man named Walter Scott was shot in the back five times and killed in North Charleston by a police officer. Scott, who had been stopped for a burnt out tail-light but had spent time in jail for not paying child support, was fleeing from the officer when he was shot. I remember getting in an argument at the time with someone who said that a person gets what they deserve if they don’t listen to the police. Unfortunately, I was mischievous, and several months later, while exploring a subterranean steam tunnel, a police officer discovered me and yelled at me to stop. Not wanting to get caught trespassing, because it put a conviction on my record, I ran. I know, I’m not painting the most flattering picture of my young adulthood… And yet, for my best friend growing up and high school cross country teammate, Benyam, he has to keep that in the back of his mind that even just around his neighborhood could lead to his death. A couple of years ago, after a string of black men were shot while exercising, Benyam published his running-while-black checklist in the Washington Post: Is my beard too thick? Is it too dark outside? Am I dressed like a runner? God forbid I wear mesh b-ball shorts and a loose T-shirt in the suburbs of Dallas. Then, while on the run, I have to consider: Is my rap music too loud? Can they hear it? Does my cap, worn backward, send the wrong message? Do I open up my stride now or wait until I get out of the neighborhood and into the open roads so I don’t appear to be running away from something or someone? How many times have I looked over my shoulder on this block? Does that look suspicious? Then there is scenario planning while running — if this, then that: -If you see a young white woman on same path, cross street immediately and try not to make eye contact twice. -If there is a white older woman/man on same path, wave/nod/smile, cross street casually. -If you’re running behind them and they don’t hear you, cough loudly/clear throat, cross street. -If the sidewalk is narrow, always give way to walkers or bikers and step into the grass or street, even though you’ve shattered your ankle twice, once on grass and once stepping into the street from the sidewalk. -Turn down volume on music when passing by neighbors. Need to be able to respond if they say something — don’t want to come off profiled as angry black man. -If a raised pickup truck approaches, immediately take to the sidewalk and get a good look at driver. High alert. Ready to dive into someone’s yard in case he swerves into me. I have never experienced what it’s like to be black in this country. I only know what it was like to grow up white in a black area of Jefferson City, Missouri, and it’s been eye opening for me. And I don’t just mean that city maintenance was neglected and that the neighborhood is now falling apart. I mean the things that people don’t say out loud or write about or pretend don’t exist. Things like people looking down on where I lived. Other kid’s parents hesitating for them to come over. White kids calling my black neighbor kids the n-word consistently throughout my school years. High school classmates telling me that I lived in “porch monkey” land. I remember being a 20-year-old Yale student back home over break and spending time on the other side of town with the fancy folks. Hanging with adults in high-up positions who oversaw hiring for their organizations and hearing them casually drop the n-word when referring to black people. It’s no surprise to me that people like that would interview white convicts for job interviews instead of black men without criminal records. This isn’t to say that everyone I interacted with held those views. The vast majority of people in my hometown were decent and cared about one another. But plenty were not, and that stacked the deck. I hope they try even bigger things some day and even if the odds are against them, as they always have been, I’ll be there for them and I hope you will be, too. Lucas You're currently a free subscriber to Lucas’s Substack. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Monday, January 20, 2025

“Please do not think we think you are not important, but…

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment