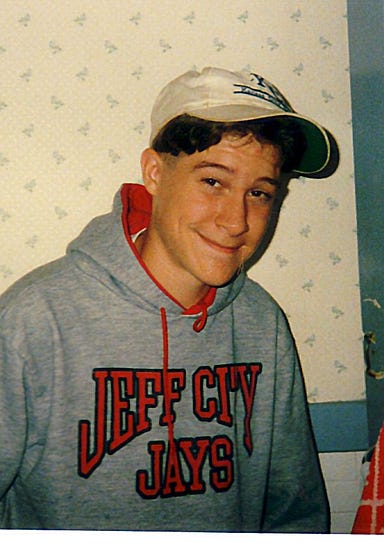

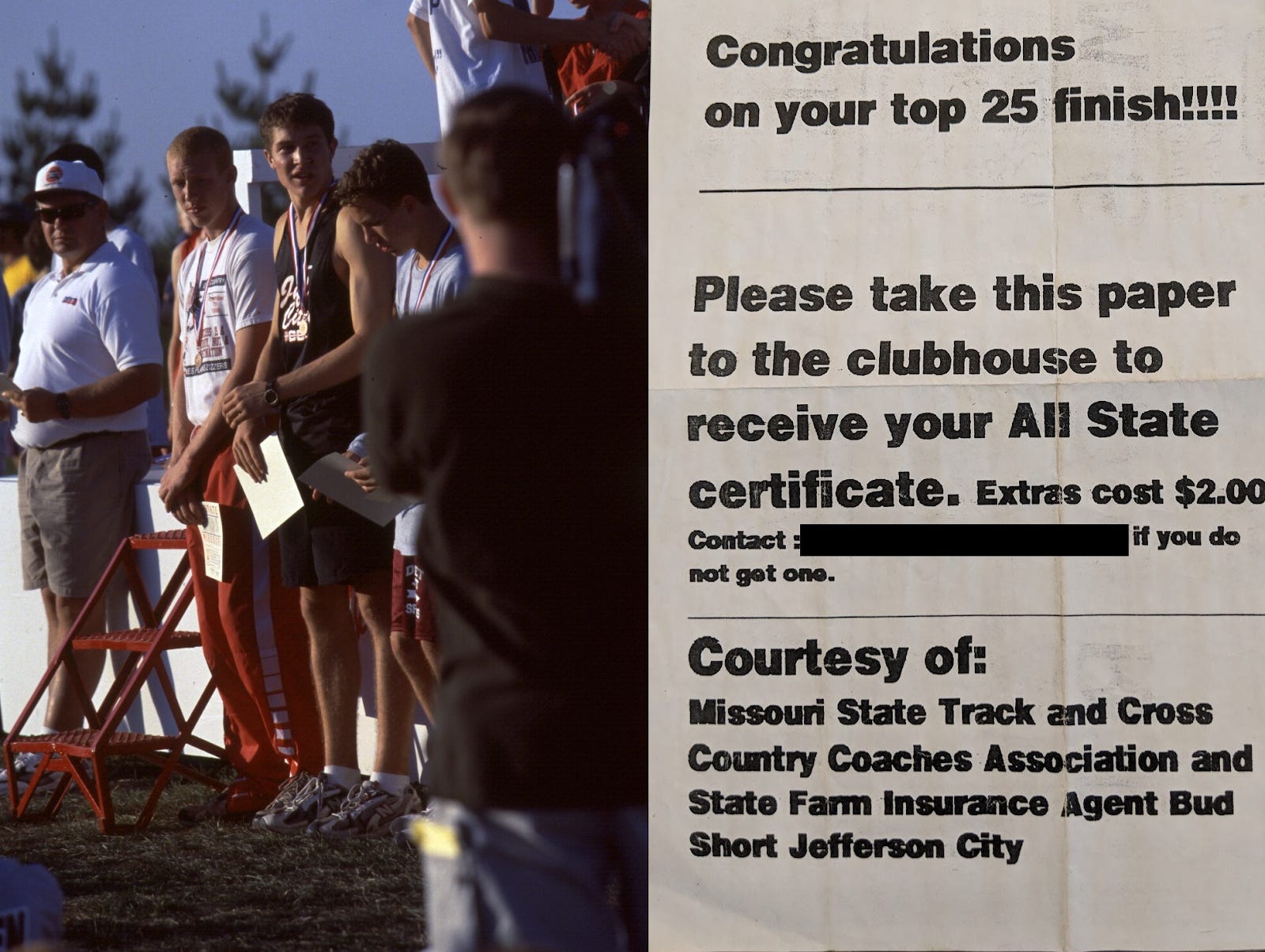

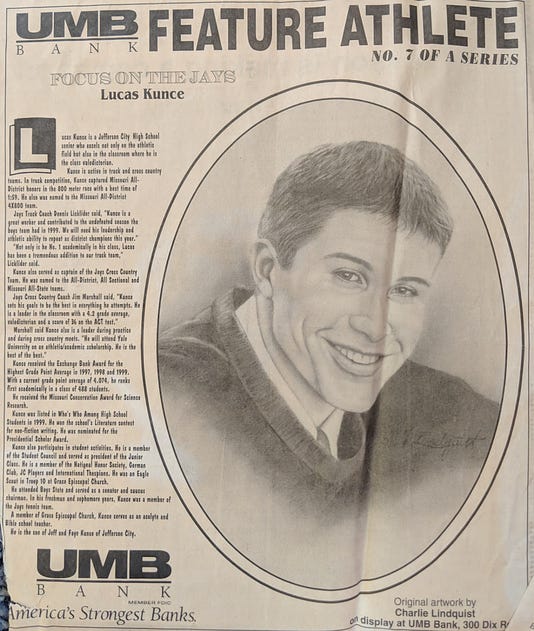

It's time to give back to the people and communities that have given all of us so muchThey invested in us. We need to invest in them.We are in the home stretch of our campaign against Josh Hawley, and recent polls show that this is just a 4 point race. Will you forward this email to your family and friends to let them read more about who I am and what I’m fighting for in this election? We still have time the close the gap and win this race — but only if we have the people-power and resources to keep spreading our message across Missouri. “I’ll be alright,” I said, flinching as I put a bag of ice on my shin and leaned back against a Jeff City High School locker. Coach looked down at me and pursed his lips. “I’ll be right back,” he said Two minutes later he returned and held something down to me. I looked at his hand and back to his face, confused. It was one of those paper concession stand Coca Cola cups. “Thanks, Coach…” I said, “but…” I nodded toward my water bottle. He lifted the cup back up to himself and brought his other hand up to it, tilting the cup sideways as he did so. Sitting right below him, I jerked instinctively, expecting the water to pour down on me. But nothing happened. Bemused, I watched as Coach tore the rim off the cup about three inches down. Then I laughed at myself. The water inside was frozen. With the rim torn off, it looked like a giant push pop sticking out of the tattered end of the cup. “This won’t fix things, but it’s a little more effective,” Coach said, “Do it like this.” And he rubbed the icy end up and down his arm then handed it back down to me. “We’ll figure this out,” he added, and walked away. It was the fall of 1998 and we were a third of the way through my junior season of high school cross country. For the first time in my running life, I was injured. But I knew that Coach, who had been there from my first high school run, really would do everything he could to figure it out. Just like my academics, my Lewis and Clark Middle School athletic career had been entirely unremarkable. I’m pretty sure the middle school coaches only knew who I was because I had gotten my ear-pierced in seventh grade and my mom gave them hell when they made me take it out and it grew over. I only decided to run cross country freshman year because my super cool older cousin, who lived in O’Fallon, Missouri, had come to Jefferson City for the state cross country meet a few years before and I wanted to be like him. I also really didn’t have anything else to do that fall. What a decision. On my first run, I paired up with a guy named R and we were given directions on where to run. It could not have been longer than three miles, but we had to stop and walk several times. We would have walked a lot more except that the girls team left on the same route a few minutes after we did and, after their leaders tormented us as they flew by, we didn’t want to be caught walking by the rest of them as they all caught up and passed us. By the first meet, Coach had us freshman to a point where we could at least run the full two miles of the freshman course. And midway through the season he had us on the occasional slow run with older guys, who we both worshiped and were terrified of. They were crazy fast — under Coach’s leadership we had become one of the top teams in the largest division in the state — and they were also just plain crazy. They would pick up discarded beer cans on long country runs and drink whatever was left in them. They chewed dip when no one was looking and gave us nicknames like “Buddy,” “Daisy,” and “Ep.” They tried to name me “Dammit,” like, “dammit run faster” or “dammit get over here,” but Coach didn’t let it stick and likewise shot down more offensive labels related to the pronunciation of my last name, which kind of just happens on its own sometimes. By the end of freshman year Coach had me running 5k in under 18 minutes, which wasn’t half bad. I might have been a varsity runner if we hadn’t been state champions that year. I tore through sophomore season and aspired to be an all-state runner like so many of the older guys. Despite leading a team that was ranked as high as 13th in the nation that year, Coach took the time to make a plan for me so that I could make it happen the next year. The summer before junior year I crushed the miles like never before and just knew we were going to make it happen. The first couple of meets made me even more certain. But then, as the mileage piled up, my shins started to break down. I’d never experienced shin splints before, so I ignored it at first, as something I could just run through. This, of course, just made it worse. One day, Coach spotted me limping during a workout and immediately stopped me. I took the next day off, but it didn’t make a difference. Shortly after he gave me the ice cup, Coach came up with a new plan to at least keep me in the mix. He got me access to the YMCA across the street from the high school. Until things got better, I ran in the deep end of the pool with a floaty belt every morning before school and was either back in the pool or on a bike each afternoon. I spent the rest of the season in and out of the pool. A doctor told me that my feet were different sizes, so maybe I could try getting the right size for each rather than splitting the difference. This came across as pretty ridiculous given that my parents could only afford one pair of shoes for the entire summer and fall as it was and everything I earned went toward gas, lunch, and saving for my future beater so that I could get to work and school on my own. I told Coach about it and we instead tried some inserts. They didn’t do much. Coach’s pool regime worked fairly well. I ran the post-season that year and helped our team medal at the state meet. And although I didn’t make all-state, I had a good showing for a guy who hadn’t run in over a month, and scored in a year where we won a 4th place State trophy. As senior year came around and I amped up my mileage that summer, I freaked out at every twinge in my shin. I told Coach about it and he told me to ice early and often and not to worry about it, he would take care of things, and he gave me the occasional morning off so I wouldn’t get too worn down. I began the year even better than the year before, but the nagging thought that the mileage would catch up was always there. I brought it up again and Coach looked at me firmly and said, “Lucas, don’t worry about it. I’ve got it figured out.” A couple weeks later he asked me to stay after practice. So I did. He avoided eye contact with me as everyone else headed out. I started to develop that knot in my stomach that you get when you know you’re in trouble for something. I wondered what it could be. He waited until everyone was gone. Then he called me over to the storage closet in the hallway where he could talk without anyone overhearing us. My stomach churned. What could it be? Coach turned toward me as I walked through the door. I guess I was going to find out the hard way. “I want you to have these,” he said quietly, “but you can’t tell anyone. Do you understand?” “Huh?” “I’ve been tracking your miles. You need to change your old ones out. But I know… well… everyone’s situation is different. Just take these and don’t tell anyone.” He shoved a cardboard box into my hands and walked out, not waiting for me to say thank you or see what it was. As he walked away I looked down. It was a new pair of running shoes. Later that fall, injury free, I proudly posed for the Jefferson City News Tribune photographer on the grounds of Oak Hills Golf Course for a photo after the state track meet, wearing my hard-earned all-state medal. Captain of the Jefferson City High School Cross Country Team. I never would have achieved that without Coach. I may have never made it to Yale without those credentials. That simple act, which was probably against some rule somewhere that makes life harder for people without money, likely changed the course of my life. And it’s not like he did it from a place of comfort. He was a middle school teacher and high school coach in a state that pays its teachers poorly. The coaches and the teachers in this state know our kids. They know our dreams, our weaknesses, and our needs. They invest in us. I saw it first-hand through my mom, who taught middle school at Eugene Cole R-V and spent what little she could scrape together on supplies to improve that classroom for the kids there when she barely had enough for her kids at home. Eventually she had to quit because she basically wasn’t making any money and my disabled little sister needed her support. These heroes sacrifice every day for the next generation of Missourians and our politicians, in turn, have rewarded them with the lowest teacher pay in the country. And now, in order to save money, many Missouri school districts are only open four days a week, making the challenge for our teachers and coaches even harder. If we don’t start investing in our teachers and coaches soon, there won’t be anyone left to invest in our kids. And that’s going to be a lot less opportunity for all of us. ### |

Tuesday, October 8, 2024

It's time to give back to the people and communities that have given all of us so much

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment